At the start of this year,

I blogged on the mechanics of a double dissolution election. At the time I concluded it was possible but not a certainty. In my mind I gave it a probability less than 50 per cent - I saw it somewhere between a 25% and 33% probability.

Since then there has been quite a bit of chatter suggesting a 2 July double dissolution. For example:

- Antony Green reported Malcolm Turnbull told the party room on 2 February that a double dissolution is a 'live option'

- Malcolm Turnbull defended the legitimacy of the double dissolution option on Insiders on 7 February.

- On 11 February, the Courier Mail suggested there is evidence for the Government considering a 2 July double dissolution election.

- In the Australian on 18 November, Nikki Savvas said, "There is still a slim possibility Turnbull, the day after the budget, will call a double-dissolution election for July."

- On 19 February, Cabinet Minister Pyne confirmed that a double dissolution is a live option.

This chatter, and the discussion of a particular date, has forced me to revise upwards the likelihood of a double dissolution. In this post I will work through the key factors as I now see them.

Tactical chatter

First, however, we should not dismiss the possibility that the chatter is simply or mostly tactical. The argument is that the passage of the legislation stalled in the

Senate is the Government's prime objective. The Government is using the double dissolution chatter to

pressure the resolve of the cross-benches to pass the stalled legislation. If there is a double dissolution, the cross-benches will face an election after two years in the Senate rather than the usual six; and it could be an election where micro-parties face a new primary-vote threshold requirement for the first time.

If the Government's objective is tactical, the success of this approach depends on the perceived credibility of the Government's statements. For the cross-benches to vote for the stalled legislation, they will need to believe that the Government is not bluffing.

It also worth noting that a tactical objective does not preclude a double dissolution. It is not inconsistent for the Government to have a preference to allow the Parliament to run its full term; but at the same time be willing to call a double dissolution election should its legislation remain stalled.

Campaign length

I covered 2016 electing timing extensively in

my earlier post. A 2 July double dissolution election is technically possible. The dissolution would need to occur on or before 11 May. It would result in at least a 52 day election campaign (seven and a half weeks), significantly longer than the 33 day minimum provided for in the Constitution (just under 5 weeks).

The conventional wisdom, since the ten-week 1984 election campaign, is that long election campaigns do not favour the government of the day. While then Prime Minister Hawke won the 1984 election, the swing against his Government was larger than most analysts expected. Many attributed the size of he swing to the length of the campaign.

On balance, the long campaign period necessary for a 2 July election suggests a double dissolution is less likely.

Senate terms

While a long-election campaign might mitigate against a double dissolution, an election after 1 July deals with a key problem with holding a double dissolution. Under section 13 of our Constitution, the terms of a Senator following a double dissolution shall be taken to begin on the first day of July preceding the day of his election.If the election was held in (say) June, the date of effect of those Senate seats would be backdated to 1 July 2015. The subsequent half-Senate election would need to be called by May 2018,

while the House of Representatives would be able to continue until mid

2019. The next government will either need to decide on an early synchronised

election in the first half of 2018, or allow House and half-Senate

elections to get out of sync from 2018 onward.

On balance, a double dissolution election on 2 July is more likely than an earlier double dissolution election. If the Government is leanings towards having a double dissolution, a 2 July election would be among the more likely dates.

Senate voting reform

According to media reports, the government appears to have negotiated a Senate voting reform proposal with the Greens and Senator Xenaphon. According to reports, voters will be required to preference vote for only six parties above the line. This six-preference limit would curtail micro-party preference harvesting.

If the Government can secure support for Senate voting reform, it should make the Senate more workable for the Coalition (there would be fewer micro-parties to negotiate with). It may even benefit the Coalition at the polls (but nothing like the extent that was

reported this week drawing on work from Graham Askey and Peter Breen).

Senate reform should mitigate the usual problem of the lower quota at a double dissolution resulting in more cross-bench Senators being elected. A normal half-Senate election in the second half of 2016, even with Senate voting reform, would see Senators Wang, Lazarus, Lambie and Muir continue in the Senate unto 30 June 2020.

On balance, if the Government can enact legislation for Senate reform before 11

May, it increases the likelihood of a double dissolution. A double

dissolution with Senate voting reform would most likely only see the

Coalition, Labor, the Greens and Senator Xenaphon's supporters remain in

the Senate.

The Budget

Perhaps the most challenging question for the Government is its operating Budget for the 2016-17 financial year. Without a Budget passed by Parliament, the Government will not be able to pay the

wages of public servants nor pay for community services from 1 July.

Pensioners would be protected, as they are paid under special

appropriations that do not need to be renewed each year through the

Budget process. But without a Budget, it is unlikely that the

Governor-General would agree to grant a double dissolution election for 2

July.

It is likely the Government has thought about this problem, and it is entirely possible that the negotiations for Senate Reform also

include an agreement to pass a supply budget in both the Senate and the

House of Representatives. The passage of a supply Budget could occur in the last week of the Autumn sittings (15-17 March), or on the first sitting day of the Winter sittings (10 May). A supply budget would give the Government 5 or 6 months of funds (simply replicating the 2015-16 Budget), with the expectation that a full budget would be brought to Parliament in August or September 2016.

Nonetheless political risks remain. Labor could argue that Turnbull Government is not telling the voters what services it plans to cut or the taxes it plans to raise. While these matters would be covered during the election campaign, the absence of a normal May Budget gives Labor a front-foot start to the election campaign. The alternative of exposing the full proposed Budget for 2016-17 prior to the election being called allows its less palatable elements to be picked over in the glare of an election campaign. The per-election economic and fiscal outlook statement would serve a similar role to the Budget-papers, updating the Government's fiscal position and forward estimates.

If the Government has done a deal to ensure the passage of the supply bills through the Senate. the need for a Budget should not impact on the likelihood of double dissolution. Without such an agreement, a 2 July double dissolution is unlikely.

The "trigger" Bills

The list of double dissolution triggers has one important change since the beginning of the year. The

Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 [No. 2] has been introduced into the Senate for a second time. The failure of the Senate to pass this Bill is likely to be the centerpiece of the Government's argument for a double dissolution.

The fact this Bill was reintroduced on 4 February increases the likelihood of there being a double dissolution.

School holidays

If an election was held on 2 July, the NT, Qld and Vic would be in the middle of their

school holidays. ACT, NSW, Tas and WA would be at the start of their school holidays.

Because school holidays can see large numbers traveling, lower voter turnout, and some dissatisfaction with the government for calling an election that interrupts holiday plans, governments often avoid calling elections during school holidays.

In this case, the planned school holidays make a double dissolution on 2 July less likely.

Conclusion

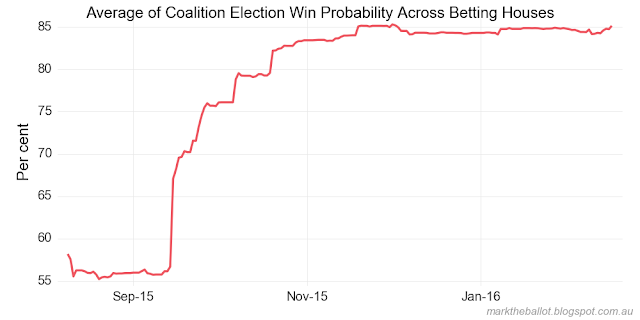

When I blogged at the beginning of the year, I thought a double dissolution election possible but unlikely. In my mind I gave it a probability of 25 to 33 per cent.

With the ongoing chatter around a double dissolution, the re-introduction of the

Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013, the rumoured passage of Senate voting reform, and the focus on an election date that does not give rise to an out-of-sync half-Senate election, I have re-evaluated the likelihood of a double dissolution.

Mediating my assessment are the length of the double dissolution election campaign, the way a Budget-free double dissolution could support a Labor narrative that the Government does not have an economic plan, the logistics for securing a supply Budget, Senate voting reform may still fall over, the timing of school holidays, and the cross-bench Senators might just blink and pass the Bills stalled in the Senate without a double dissolution.

On balance, I now estimate the probability of a double dissolution election to be somewhere between a 40 and 50 per cent probability. Still less likely than more likely; but significantly more likely than I thought at the beginning of January.

Updates

I have corrected the school holidays.